The Federal Reserve regularly reports on the college wage premium in America.

It is a signature mechanism researchers use to establish the value of college.

This essay examines the research and use of this common research measure. Does the college wage premium help us reach a definitive conclusion on the question of college value?

Read on to find out.

“Every man has a right to his opinion, but no man has a right to be wrong in his facts.”

Bernard Baruch

The College Wage Premium describes the difference in earnings between a college graduate and a high school graduate.(1)

It’s a popular term. Search Google, and you get more than 15 million results.

Researchers, policymakers, and the media often use this popular metric to advocate for the value of a college degree.

These publishers generally argue that the college wage premium identifies a substantial earnings advantage for workers with a bachelor’s degree over those with only a high school diploma.

The frequent claim is that this advantage is so substantial that a college degree makes sense for most high school graduates.

Their powerful argument for college attendance works.

Nearly 3 million high school students graduated from high school in 2022. Sixty-two percent chose to attend college (2). That year, 13.5 million students were in undergraduate programs (3).

But what if these publishers need to be corrected?

What if the College Wage Premium, the metric these influencers hold in such high regard, is not as definitive as they believe? What if it’s leading them astray?

What if it fails to provide a clear answer on the financial worth of a college degree?

What if many Americans who rely on the advice of the pundits are operating under misconceptions about their college investment?

I will tackle these critical questions in this article. But before we do so, let’s clarify what the college wage premium means.

What is the college wage premium?

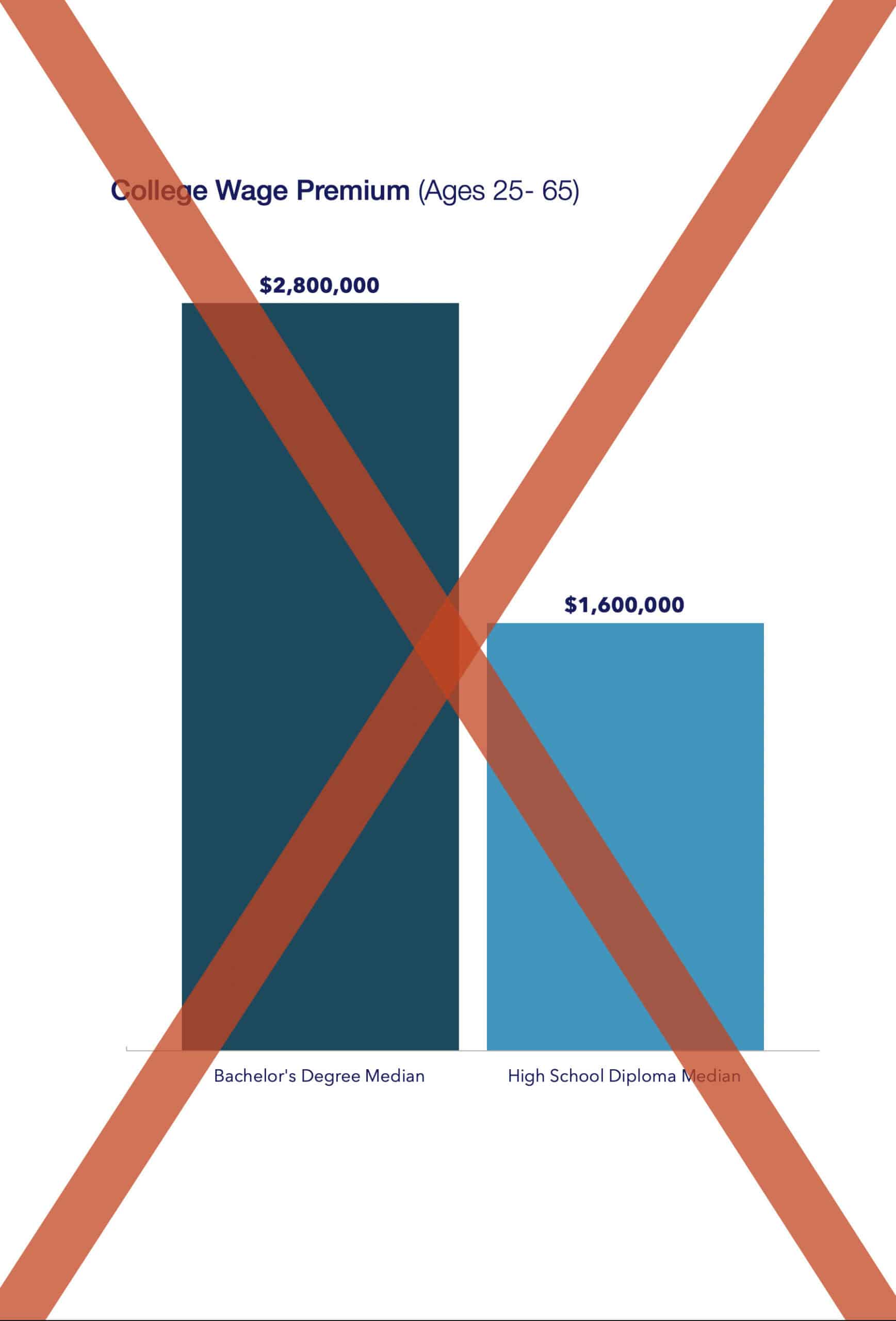

The college wage premium compares the median earnings of a college graduate to those of a high school graduate. I have seen it published in three different versions: as a percent advantage, an absolute dollar difference, or a cumulative advantage over the lifetime of each. Here are examples of each version:

- The college wage premium is expressed as a percentage advantage. This Federal Reserve article (4) says: “The college wage premium is typically defined as the percentage difference between average wages earned by workers with a four-year college degree and those by workers with a high school diploma.” They say, “Although wages differ substantially among individuals within the broad college and high school groups, we focus on this overall comparison because it can provide useful insights about the decision to attend college and its economic implications.”

- In 2022, they estimated the college wage premium to be 75%. According to their measure, the median college graduate earned 75% more than the median high school graduate.

- The college wage premium is expressed as an absolute dollar advantage. This New American article (5) is typical of this version and says: “On average, recent college graduates earn $52,000 per year, while young workers with high school diplomas but no higher education credential earn only $30,000 per year. The difference in wages between college and high school graduates – often referred to as the college wage premium – has increased since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.” In this version, the college wage premium is $22,000 per year.

- The college wage premium is expressed as an absolute dollar earned over a lifetime. An article from The Association of Public and Land-grant Universities (6) exemplifies this. They say: “College graduates on average make $1.2 million more over their lifetime.“

Okay. I hear you saying that you understand these and need help to see how these metrics can be misleading. After all, if one can make 75% more, $22,000 per year more, or $1.2 million more over one’s lifetime by attending college, why doesn’t that prove it’s a good idea?

Simply put, these pundits declare that the gap is significant in favor of the college graduate, implying that most college graduates are better off than high school graduates.

It’s important to note that the College Wage Premium, while a widely used metric, has its limitations. It focuses on the median earnings, which can be misleading due to significant wage variability. Even if the gap between college and high school graduates’ earnings is large, the College Wage Premium fails to provide a comprehensive answer to the question of college worth as it overlooks other crucial factors.

What’s wrong with the data?

When I began evaluating the worth of a college degree over a decade ago, I meticulously selected the most authoritative sources available: the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the Census, the US Department of Education, and other government sources. These sources provide comprehensive and reliable data to build our models, which we update regularly to ensure accuracy and relevance.

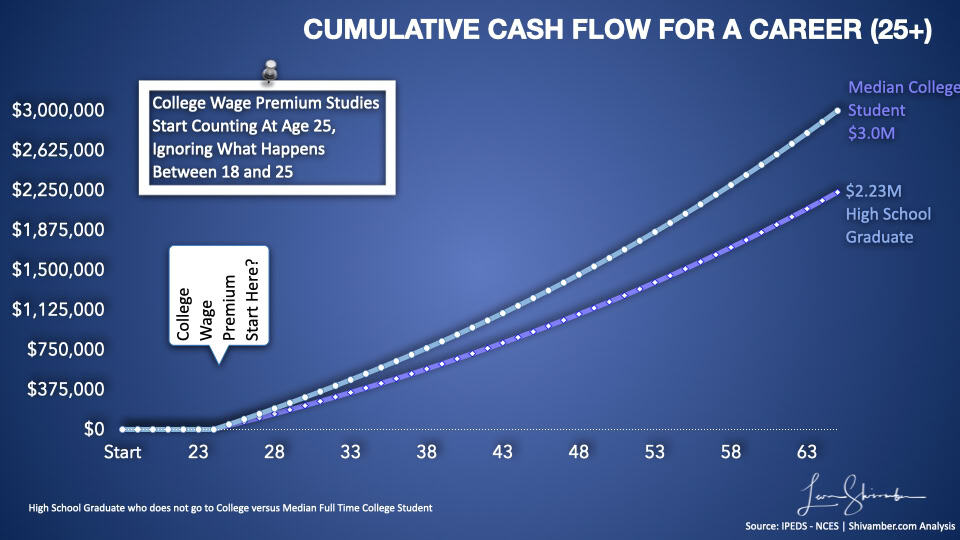

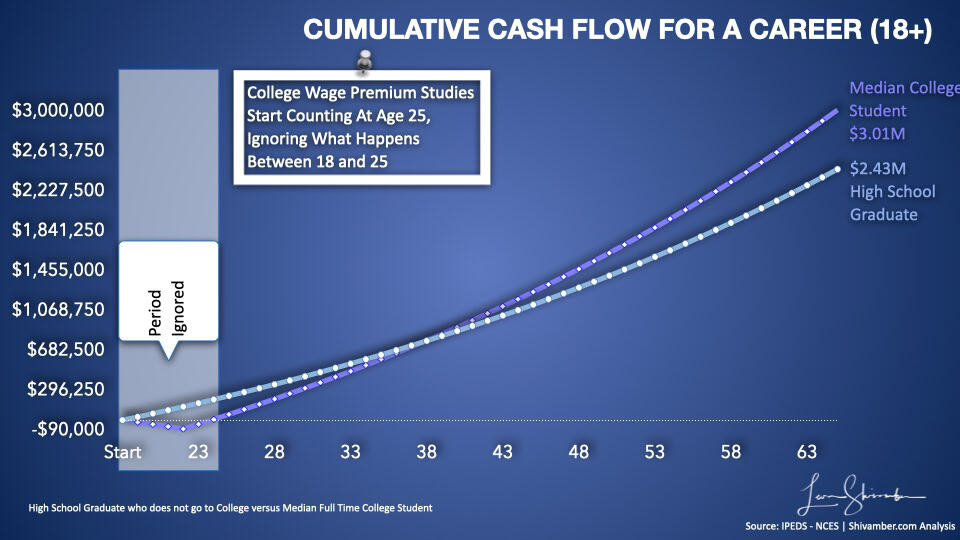

The first, most apparent error in comparison is the period used. The Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce, in their popular recent report: The College Payoff, shows a premium of $964 thousand. They say: “We reproduced the methodology originally used in the 2002 Census report on lifetime earnings.” They describe this approach as: “Synthetic estimates of work-life earnings are created by using the working population’s 1-year annual earnings and summing their age-specific average earnings for people ages 25 to 64 years.”(7)

They say: “We present our findings in dollar totals over a career, which is defined as being a full-time, full-year worker from 25 to 64 years old.“

What about the period from 19 to 25, when the high school graduate is working?

The traditional comparison ultimately leaves out the most favorable period for the high school graduate!

Our most recent model, as of May 2024, shows the median College Graduate salary at $50,806 upon graduation.

The median comparable high school graduate salary is $36,000.

Our estimate of the college wage premium is $14,806, which is 40% above the median high school graduate earnings. The lifetime college wage premium for the median is $574 thousand.

Okay, you say. You understand the gap could be smaller when the data is appropriately sourced and aligned. But you still think I am quibbling. After all, there is a premium, and even by my account, my lifetime earnings are nearly $600 thousand higher in favor of the college graduate.

You may be willing to concede that the pundits exaggerate. However, their general conclusion is still correct. Right?

What are you missing?

Let’s get into that. So far, we have established a baseline understanding of the college wage premium.

The problem is that even when we know the accurate college wage premium, we still need to determine whether a college degree is worth it.

Let’s use an example to explain what’s wrong with using the college premium.

An Investment Example

Let’s assume you are thinking of becoming a real estate investor. You have heard real estate is profitable and have been exploring some investment choices, such as buying and renting a building to tenants.

You have narrowed your choices down to two.

The first choice is Building A, which is in your neighborhood and for which you have enough money to buy.

The second choice, Building B, is in a nicer neighborhood, but you must spend more to buy it. Your parents may have to give you the extra money, or you could get a loan for this investment.

You have trusted advisors helping you evaluate these investments, and you are eager to determine how they compare.

Your advisors tell you that Building B is a significantly better choice. You can get 75% more rent with building B than with building A. That means you will receive an extra $22,000 in rent each year. And that adds up to an additional $1.2 million of rent you will receive over the next 40 or so years.

What would you do? Which is the better investment, building A or B?

If that were all the information needed, one would always choose the building that generated more rent. But you know something is missing in the equation. There is something essential you need to consider before you can decide.

What’s missing? The costs. More precisely, the extra costs of buying building B.

Before deciding, you must know whether the additional rent is enough to cover the extra costs of buying Building B.

Similarly, the college wage premium fails to establish whether a college degree is worth pursuing because it never addresses the cost of attending college.

To determine whether college is worth it, we must ensure that extra earnings (i.e., the college wage premium) make up for college costs. I can see the wheel turning. You concede that the college wage premium alone is not enough. Still, you need more time to be ready to question the pundits’ conclusions.

After all, these are bankers, economists, financial writers, and even college researchers and presidents.

Then you point out that my analysis of the lifetime college wage premium of $574 thousand suggests it’s worth it because no college costs that much.

Sadly, you have fallen for the same mistake all these pundits make. They find a large gap because they are imprecise when calculating the college wage premium and assume the details don’t matter.

But the details matter. In fact, in many cases, a college graduate earning $574 thousand more than a high school graduate is not enough to make it a better choice.

Let’s dig into the details that the researchers miss that make their conclusions wrong.

What details do college wage premium pundits get wrong?

Most discussions about college worth get three things wrong:

- They either ignore college costs or underestimate them.

- They don’t factor in the impact of taxes on the wage gap.

- They ignore the time value of money.

Understanding College Costs

College tuition, fees, and living expenses range from free to a maximum of about $100,000. And so, most pundits conclude that their $1.2 million (our $574 thousand) lifetime incremental college wage premium more than makes up for the maximum case of $400,000 if you go to one of those elite schools and pay full fare.

However, college tuition, fees, and living expenses are not the only costs incurred. There is also the opportunity cost associated with attending college. Most college students attend classes full-time for four years or more before graduating. While they are in college, high school graduates who go to work right after graduation will earn four or more years of earnings. In other words, a college student foregoes a salary they could have earned otherwise. Over four years, this could amount to approximately $160,000.

So, all-inclusive college costs range from $160,000 to $560,000, with a median of approximately $240,000.

Aha, you say. So even when we are more precise and add opportunity costs, those costs are still below the $574 thousand premium.

I agree. However, your argument was a lot better when you thought it was $1.2 million, but that gap is shrinking rapidly. The gap has mostly disappeared for someone paying the full cost of an expensive college.

The gap disappears when we consider the additional effects we discuss next.

The impact of taxes

In the United States, we have a progressive tax system. The more you earn, the higher the tax rate you pay. The result is that taxes on higher income increase faster than the income itself.

First, we pay Social Security and Medicare taxes on our earnings (up to a specific limit). Then, we pay federal and City/State taxes when applicable.

In 2024, you pay marginal taxes of 10% on the first $11,000 of income (after deductions). That rate goes to 12% between $11,000 and $47,150 and 22% between $47,150 and $100,525.

The result is that while a college graduate may earn more than a high school graduate in a given year, they don’t get to take home all of the premium. In the early years after graduation, a high school graduate could find themselves in the 12% tax bracket, while a college graduate is in the 22% tax bracket or higher.

Remember that $574 thousand premium I mentioned earlier? It shrinks to $391 thousand after taxes.

Taxes shrink the college wage premium significantly.

Time value of money

Most estimates of the college wage premium compare the median earnings of college graduates to the median earnings of high school graduates. There are several variations of this data. As a result, the median is several years after high school and college graduation, respectively.

It’s unlikely that the medians represent graduates of the same age. The result is a frequently inflated gap that compares earnings well after graduation.

A more accurate analysis shows a much smaller gap at the beginning of their careers and a growing gap later. In the example above, adding small gaps at the beginning and more significant gaps at the end could add up to a $574 thousand lifetime.

The timing of the gaps matters. They matter because of the time value of money. Simply put, a dollar today is worth much more than a dollar next year or forty years from now.

Every economist knows that using a discount cash flow model is the most accurate way to standardize when money is spent and earned at different times. That means we have to take all the gaps and estimate what they would be worth on a specific date, such as the beginning of the investment. In this case, the most accurate comparison method would be to take the earnings after taxes each year and estimate what they would be worth at the beginning (i.e., the high school graduation date).

When you use a discount cash flow model to standardize the median college graduate costs and earnings and compare it to those of a median high school graduate, you will find that the pundits are wrong.

We estimate the median college graduate’s net present value of costs and earnings before taxes at $463 thousand. For a high school graduate, that number is $505 thousand! After taxes, the college graduate’s NPV is $373 thousand, while the High School Graduate’s is $430 thousand.

What does this mean?

This lower NPV means the median college student is not earning a hefty enough premium after graduation (after taxes and discounted to today’s value) to offset the college investment. The result is a lower Net Present Value of Lifetime earnings (after taxes) than that of the median High School Graduate.

This result means that some college degrees do not generate a value greater than that of a high school graduate, despite the more significant income earned in a lifetime.

This result does not mean college degrees are not worth pursuing. Many are, depending on the chosen college, field of study, fees paid, and academic capability of the student. However, one should only assume one’s choice will work by adequately evaluating the details.

Conclusion

A college investment is a complicated financial decision. For some, it’s the most significant financial decision they may make in their lifetime.

Using simplistic models to push a particular choice when making that decision is not helpful.

The college wage premium does not tell you whether a college degree will be worth it to you financially.

It tells you that the median college graduate makes more than the median high school graduate. That’s all it tells you.

Pundits, researchers, policymakers, and all other influencers should stop using the college wage premium to reach conclusions that it does not support.

Reference Sources

- Note: The Bureau of Labor Statistics provides data for calculating a version of the college wage premium. On this page: https://www.bls.gov/emp/chart-unemployment-earnings-education.htm, as of September 2023, they list College median Weekly salaries at $1,493 and High School Median Salaries at $899. Their college wage premium is $30,888 annually or 66%. They identify the median for full-time workers aged 25 or higher in these categories. We do not know if the medians represent similarly aged workers or how old they are. The median is significantly older than 25.

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. ”College Enrollment and Work Activity of Recent High School and College Graduates Summary.” Bls.Gov. April 23, 2024. https://www.bls.gov/news.release/hsgec.nr0.htm.

- United States Census Bureau. ”School Enrollment Data.” Census.Gov. Accessed July 10, 2024. https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/demo/tables/school-enrollment/2022/2022-cps/Tab05-2022.xlsx.

- Valletta, Robert G., Leila Bengali, Marcus Sander and Cindy Zhao. 2014. Falling College Wage Premiums by Are and Ethnicity” FRBSF Economic Letter 2023-22, August 28. https://www.frbsf.org/research-and-insights/publications/economic-letter/2023/08/falling-college-wage-premiums-by-race-and-ethnicity/.

- Geary, Chris. “College Pays Off. But by How Much Depends on Race, Gender, and Type of Degree.” Newamerica.Org. New America, March 1, 2022. https://www.newamerica.org/education-policy/edcentral/college-pays-off/.

- https://www.aplu.org/our-work/4-policy-and-advocacy/publicuvalues/employment-earnings

- Anthony P. Carnevale, Ban Cheah, and Emma Wenzinger. The College Payoff: More Education Doesn’t Always Mean More Earnings. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce, 2021. cew.georgetown.edu/ collegepayoff2021.